I really love Danish modern furniture. Flowing lines, elements reduced to pure function and fundamental proportion, a focus on the beauty of the wood itself. The turned legs on this piece were a central element, but I found myself feeling vexed by the prospect of attaching them to the case. This shouldn’t be the hard part, right? I haven’t had the chance to crawl around underneath many quality pieces from this era to see what the Danes would have done, and I was really perplexed. I have seen a few sofas with a stretcher system tenoned into the legs, but I wanted these legs to join directly to the bottom with nothing interrupting the flow, even when viewed from a low angle. The prospect of sawing them flush and bolting through the bottom was unacceptable. I needed an elegant and extremely strong solution with no metal fasteners, so I turned to Windsor chair joinery for the answer.

Windsor legs are joined to the seat with tapered tenons, but in this case there were a few wrinkles to iron out. The bottom of my case was only 3/4″ thick, which is ok but a little thin for a truly strong joint. Also, I wanted a shoulder on these legs so that they would meet the case bottom solidly at their widest dimension, as opposed to most Windsor legs which taper down as they meet the underside of the seat. My solution was to add a round “puck” of wood to each leg location to both thicken the structure and to provide a landing pad perpendicular to the centerline angle of the leg. A few pictures:

I sawed some 3/4″ material with a compound angle on the ends to match my resultant and sighting angles for the legs, with the grain direction matching the bottom of the case. These angles derive from the rake and splay angles of the legs as viewed from the front and side-for an explanation of this angle jargon, take a look at a blog post by Peter Galbert, an amazing Windsor chairmaker: http://chairnotes.blogspot.com/2012/04/ive-been-all-over-map-lately-but-i-am.html Once the wood pucks were glued in place, I drilled 3/4″ holes for the legs and reamed them with my 6 degree reamer made by Tim Manney, another great chair and tool maker: http://timmanneychairmaker.blogspot.com/

I used a carving gouge to shape the pucks back from the point where the legs meet the landing pad-this maintained the added strength of the assembly while smoothing the transition.

Combining a tapered tenon with a shouldered tenon might seem illogical-using one or the other would seem to make better sense. However, I felt in this case that it works because of the ability to tune the tapered fit to a very fine tolerance. I tapered the mortise until the hand fit leg bottomed out solidly with a 3/64″ gap between the shoulder and the landing-on assembly a final hammer blow drove the shoulder tight, leaving a snug mortise/tenon assembly and a tight shoulder. This was hot hide glued and finished with a maple wedge from the inside of the case.

Here is the case bottom with legs glued, back edge rabbeted, front edge routed for sliding door runner, and partition locations doweled.

I’m optimistic about the strength of this leg joint and love the way the legs appear to grow from the bottom of the case.

Next, the partitions were glued in place and the dovetailed box glued together. Getting closer to the finish line now!

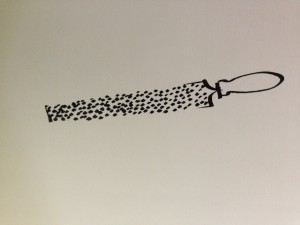

The triangular recessed door pulls were fun-I drew them without much thought and figured I’d seen them somewhere else. I even searched the internet for a while trying to find a similar design, to no avail. The angles matched the splay of the legs and just looked good to my eyes. Well, perhaps I invented them, although I do believe there is nothing new under the sun…

I’m a low tech woodworker and I somewhat despise reaching for the router, but in this case it was the perfect tool for the job. I used a dovetail bit with two collars to template route the recess and give the pull an undercut edge for good grip.

Making the template was easy, I simply raised the tablesaw blade with the workpiece against the fence for the straight baseline cut. I drew the angles on the template, extending them all the way across the board. Then I lined the marks up with the kerf slot on my crosscut sled and again raised the blade to make the cuts. A small piece of wood fills the kerf at the shallow angle apex. I routed the recess with two different sized collars, starting with a larger diameter until I got to full depth, then finishing with the smaller collar for a final pass. This preserved the correct angle at the edge of the recess. A practice mortise in scrap wood helped me figure this out before ruining my doors!

Now it was on to the back-I pondered 1/4″ plywood for about one second. Nope-wasn’t gonna happen. I glanced around the shop-so far I had made this whole piece from the single walnut log, and I wished I could finish this way! I had a stack of knotty, sappy, gnarly cut-offs lying by the bandsaw, dangerously close to the woodstove. Inspiration struck and I thought to resaw them and create a ship-lap back 1/4″ thick. As I resawed the boards I was amazed at the beauty of the material.

Suddenly knots and holes became landscapes and cat faces, winged angels and waves of light. I laid out the resawn boards and had another burst of inspiration. As I set the center boards in a book-matched configuration, I realized that I could continue the book-match outward all the way to the edges of the cabinet. I played with the arrangement and pondered the balance. Shuffling boards and composing with the grain is a meditation of sorts, listening to inner voices and waiting until things just feel right.

Once the back boards were ship-lapped and fit, I had another light bulb click on regarding the access holes. This being a hifi/media cabinet, access for power cords and cables was needed. Drilling round holes didn’t seem to fit with the level of refinement the back was receiving, so I pondered other shapes. The door pulls! I turned the triangle horizontally for a top center access, and added a smaller right triangle in each bottom corner. I attached the back with little brass screws. I like the riveted effect of the fasteners.

in the end, I find the back of this piece to be perhaps more interesting than the front, and I love the idea that it can be used away from a wall without shame. Cracks and knots and holes, sap and splits and wild swirls of grain-I love it all. The soul of a tree.

While delivering this piece of furniture to its new owners I reflected on how much I had enjoyed building it, and how the piece itself seemed to be speaking to me all along, one idea growing into the next. It’s a humble piece of casework, honest and unpretentious, built to last. It all began with one walnut log…